|

|

|

||

|

Charleston S.C. "1860 - 1865" |

||

|

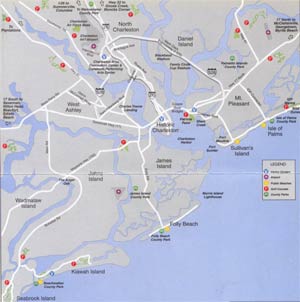

The History of Charleston, South Carolina Charleston, South Carolina is located directly on the Atlantic Ocean in Southeastern region of the United States. In 1670, Charlestown or Charles Towne Landing was established. In 1690 it was moved from Charlestowne Landing west of the Ashley River to the peninsula of present day downtown Charleston. In 1800, Charleston was the fifth largest city in North America, behind only Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Quebec City. In 1783, it adopted its present name, Charleston. Known as The Holy City, Charleston offers great historic secrets and folklore. Culturally unique, Charleston is located at the mid-point of South Carolina's coastline, at the junction of the Cooper and Ashley Rivers. Charleston's name is derived from Charles Town, after King Charles II of England. The State’s nickname is "The Palmetto State" after the Palmetto Palm tree which flourishes in the area. The Ashley River meets with the Cooper River in Charleston harbor before discharging into the Atlantic Ocean. After Charles II of England was reinstated to the English throne, he granted the chartered Carolina territory to eight of his loyal subjects and personal friends, known as the Lords Proprietor, in 1663. Seven years later, the Lords arranged to establish the settlement of Charles Towne. In 1670, the community leaders moved the city of Charles Towne across the Ashley River to the city's current location. Anthony Ashley-Cooper, one of the Lords Proprietor, decreed that Charleston become a "great port towne." In 1680, the settlement was joined by other settlers from England, Barbados, and Virginia, and relocated to its current peninsular location. Charleston was the capital of the Carolina colony and the center for further expansion and the southernmost point of English exploration during the late 1600s. Charleston was often attacked from sea and from land by both Spain and France, who still contested England's claims to the region. Also, this was combined with resistance from Native Americans as well as famous pirate raids. Charleston's colonists built a fortification wall around Charleston to protect it from these attack and intruders. The Grand Modell, in 1680, devised a plan for the new settlement presented "the model of an exact regular town," and the future for the growing community. Land surrounding the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets was dedicated as a Civic Square to the Four Corners of the Law, referring to the various arms of governmental and religious law presiding over Charleston. St. Michael's Episcopal, Charleston's oldest and most notable church was built in 1753. Its prominent position and elegant architecture signified to Charleston's citizens and visitors its importance in the British colonies. Provincial court met on the ground floor, the Commons House of Assembly and the Royal Governor's Council Chamber met on the second floor. Charleston was home to a mixture of ethnic cultures and religious groups, although the original settlers mainly came from England. In colonial times, Boston and Charleston were sister cities, and the people who could afford it spent summers in Boston and winters in Charleston. Charleston had a great deal of trade with the Caribbean Islands, especially Bermuda, which caused many people to emigrate from those areas. French, Irish, Scottish and Germans migrated to the growing Charleston area with numerous Protestant denominations, as well as Judaism and Catholicism. Sephardic Jews migrated to Charleston in such large numbers that Charleston became one of the largest Jewish communities in North America. In 1682, the Jewish Coming Street Cemetery broke ground on their first burial plot, which attests to their long-standing occupation in the community. In 1682, the first Anglican Church, St. Philip's Episcopal, was built, destroyed by fire later and relocated to its current location. Black slaves, in 1797, comprised a major portion of the Charleston population, and were active in the city's religious community. Freed black Charleston area slaves helped established the Old Bethel United Methodist Church and the congregation of the Emanuel A.M.E. Church stems from a religious group organized solely by African Americans, free and slaves. Charleston, by 1850, had become a bustling harbor of business and trade. It was also the largest and wealthiest city south of Philadelphia. Indigo and rice were being successfully cultivated by gentleman planters at the coastal Lowcountry plantations, while merchants profited from the lucrative shipping industry. The colonists and England’s relationship deteriorated and Charleston became a focal point for the ensuing America Revolution. In 1773, in protest of the Tea Act of 1773, which embodied the concept of taxation without representation, Charlestonians confiscated tea at the Exchange and Custom House. In 1774, Representatives from the colony came to the Exchange, to elect delegates to the Continental Congress, the representatives responsible for drafting the Declaration of Independence; and South Carolina declared its independence from the crown of England, on the steps of the Exchange. Charleston and its tall church steeples, especially St. Michael's, became the favorite targets for British war ships causing rebel forces to paint the steeples black to hide in the night skies. In 1776, a siege on Charleston was successfully defended by William Moultrie from Sullivan's Island, but by 1780, Charleston fell to British control for approximately two and a half years. In 1792, the British retreated and the city’s name was officially changed to Charleston. By 1788, Carolinians were meeting at the Capitol building for the Constitutional Ratification Convention, and while there was support for a strong Federal Government, dissension arose over the location of the new State Capital and a very suspicious fire burned the Capitol building during the Convention, after which the delegates removed to the Exchange and decreed Columbia the new South Carolina State Capital. In 1792, the Capitol building had been rebuilt and became the new Charleston County Courthouse. The city now possessed all the public buildings necessary to be transformed from a colonial capital to the center of the antebellum South. Both the grandeur and number of buildings erected in the following century reflect the optimism, pride, and civic destiny that many Charlestonians felt for their community. In 1774, the Continental Congress was the federal legislature of the Thirteen Colonies and later of the United States from 1774 to 1789, a period that included the American Revolutionary War and the Articles of Confederation, which announced to the world that The Thirteen Colonies had declared themselves independent of the Kingdom of Great Britain. Charleston quickly grew wealthy from its prosperous shipping and agricultural products and the community's cultural and social opportunities, especially for the elite business merchants, plantation owners and planters. In 1736, the first theater building in America was built in Charleston, but was later replaced by the 19th-century Planter's Hotel where wealthy planters played and stayed during Charleston's horse-racing season (now the Dock Street Theatre). Many different benevolent societies were established by several different ethnic groups: the South Carolina Society, founded by French Huguenots in 1737; the German Friendly Society, founded in 1766; and the Hibernian Society, founded by Irish immigrants in 1801. The Charleston Library Society was established in 1748 by a group of wealthy Charlestonians who wished to learn more about the scientific and philosophical issues of the day. In 1770, this group also helped establish the College of Charleston, the oldest college in South Carolina and the 13th oldest in the United States. Charleston became even more prosperous during the plantation-dominated economy of the post-Revolutionary years. In 1793, the invention of the cotton gin, a machine invented by American Eli Whitney to mechanize the production of cotton fiber thereby revolutionizing cotton production, quickly made South Carolina a major exporter. Slave labor was started to help off-set the lack of workers to harvest the crops produced by the large plantations. Slaves worked as domestics, artisans, laborers and market workers. Native language to the Charleston black slavers was Gullah; a dialect based on African American structures combined African, Portuguese, and English words. The population of Charleston in 1820 was held by a black majority. In 1822, a massive slave revolt planned by Denmark Vesey, a free black, was discovered. Such hysteria ensued among the white Charlestonians and Carolinians that the future activities of most free blacks and slaves were severely restricted. Hundreds of blacks, both free and slave, as well as some white supporters were involved in the planned uprising in the Old Jail. It also was the beginning of the construction of a new State Arsenal in Charleston. As Charleston's government, society and industry grew, commercial institutions were established to support the community's aspirations. The Bank of South Carolina, the second oldest building constructed as a bank in the nation, was established here in 1798. Branches of the First and Second Bank of the United States were also located in Charleston in 1800 and 1817. While the First Bank was converted to City Hall by 1818, the Second Bank proved to be a vital part of the community as it was the only bank in the city equipped to handle the international transactions so crucial to the export trade. By 1840, the Market Hall and Sheds, where fresh meat and produce were brought daily, became the commercial hub of the city. The slave trade also depended on the port of Charleston, where ships could be unloaded and the slaves sold at markets. In the first half of the 19th century, South Carolinians became more devoted to the idea that state's rights were superior to the Federal government's authority. Buildings such as the Marine Hospital ignited controversy over the degree in which the Federal government should be involved in South Carolina's government, society, and commerce. During this period over 90 percent of Federal funding was generated from import duties, collected by custom houses such as the one in Charleston. In 1832 South Carolina passed an ordinance of nullification, a procedure in which a state could in effect repeal a Federal law, directed against the most recent tariff acts. Soon Federal soldiers were dispensed to Charleston's forts and began to collect tariffs by force. A compromise was reached by which the tariffs would be gradually reduced, but the underlying argument over state's rights would continue to escalate in the coming decades. Charleston remained one of the busiest port cities in the country, and the construction of a new, larger United States Custom House began in 1849, but its construction was interrupted by the events of the Civil War. Prior to the 1860 election, the National Democratic Convention convened in Charleston. Hibernian Hall served as the headquarters for the delegates supporting Stephen A. Douglas, who it was hoped would bridge the gap between the northern and southern delegates on the issue of extending slavery to the territories. The convention disintegrated when delegates were unable to summon a two-thirds majority for any candidate. This divisiveness resulted in a split in the Democratic Party, and the election of Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate nicknamed Honest Abe, the Rail Splitter, and the Great Emancipator, who was the 16th (1861–1865) President of the United States, and the first president from the Republican Party. The South Carolina legislature, on December 20, 1860, was the first state to vote for secession from the Union. They asserted that one of the causes was the election to the presidency of a man "whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery." Charleston’s own Citadel cadets fired the first shots of the American Civil War, on January 9, 1861, when they opened fire on a Union ship "The White Star" entering Charleston's harbor. Shore batteries under the command of General Pierre G. T. Beauregard, on April 12, 1861 opened fire on the Union-held Fort Sumter in the harbor. The Union commander Major Robert Anderson, after a 34-hour bombardment, surrendered the fort to Cadets from the Citadel, South Carolina's military college. The Citadel continued to help aid the Confederate army by manufacturing ammunition, protecting arms depots, helping drill recruits and guarding Union prisoners. Fort Moultrie is the name of the fort on Sullivan’s Island, built to protect the city of Charleston. Ft. Sumter was named after General Thomas Sumter. In 1863, Fort Sumter became the center for blockade running and was the site of the first submarine warfare between the CSS Hunley and the Union warship, the Housatonic. Union troops invaded Charleston in 1865 and took back control of many forts, such as the United States Arsenal which the Confederate army had seized at the beginning of the war. Union forces came mostly from the 23 northern states of the Union – and the newly-formed Confederate States of America, which consisted of 11 southern states that had declared their secession. Federal forces remained in Charleston during the city's reconstruction. The war had shattered the prosperity of the antebellum Charleston and the south in general. Freed slaves were faced with discrimination and poverty. Slowly business, trade and industry brought the city and its inhabitants back to a renewed vitality and growth. Charlestonians worked to restore their community institutions. In 1867 Charleston's first free secondary school for blacks was established, the Avery Institute. General William T. Sherman lent his support to the conversion of the United States Arsenal into the Porter Military Academy, an educational facility for former soldiers and boys left orphaned or destitute by the war. Porter Military Academy later joined with Gaud School and is now a well-known K-12 prep school. In 1889, a new city hospital was built for the city's aged and infirm. The United States Post Office and Courthouse, an elaborate public building was completed in 1896 and signaled renewed life into Charleston. On August 25, 1885, a 125 mile-an-hour hurricane hit Charleston destroying or damaging approximately 90 percent of the homes and causing an estimated $2 million in damages. Also in 1886, Charleston was nearly destroyed by a major earthquake that was felt as far away as Bermuda and Boston. It damaged approximately 2,000 buildings and caused $6 million worth of damage, while in the whole city the buildings were only valued at approximately $24 million total. Charleston has survived wars, hurricanes, earthquakes, tornados, many fires and urban renewal. Many of Charleston's historic buildings remain intact today. Charleston Today: Charlestonians today fondly refer to their city as The Holy City, and describe it as the site where the "Ashley and Cooper Rivers merge to form the Atlantic Ocean." Marjabelle Young Stewart, America’s most-published etiquette expert, recognized Charleston since 1995 as the "best-mannered" city in the US, a claim lent credence by the fact that it has the only Livability Court in the country. Charleston today is a major tourist destination. History combined with beautiful scenic streets lined with grand live oaks draped in Spanish moss. At the Battery on Charleston harbor is the renowned "Rainbow Row," which are beautiful and historic pastel-colored homes on the waterfront. Charleston is one of the busiest ports in the world and the majority of large container ships now dock at the Wando Terminal in Mount Pleasant. The Wando River and the Cooper River meet at the Southern point of Daniel Island. A new Cooper River bridge is under construction and due to in the summer of 2005. The new Arthur Ravenel Bridge, when completed will be the largest cable-stayed bridge in North America. Charleston annually hosts Spoleto Festival USA, an annual festival of the arts held since 1977. Other special annual events include the Southeastern Wildlife Exposition, the Family Circle Tennis Cup, the Cooper River Bridge Run, the South Carolina Aquarium, the Audubon Swamp Garden or Cypress Gardens, the Old Exchange Building, Fort Moultrie, Fort Sumter, or any of the several beautiful Southern Plantations including Boone Hall Plantation, Middleton Place, and Magnolia Plantation, founded in 1676 on the Ashley River and one of the oldest plantations in the south. In 1989, Hurricane Hugo hit Charleston, damaging approximately 75% of the homes in Charleston's historic district. The hurricane caused over $2.8 billion in damage. SPAWAR (US Navy Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command), in 2004 became the largest employer in the Charleston metropolitan area. Previously the Medical University of South Carolina was the largest Charleston employer. The Medical University of South Carolina was established in 1824 as a small private college for the training of physicians. Charleston International Airport serves the Charleston metropolitan area and is located approximately fifteen miles from west of downtown Charleston. The Census Bureau estimated the population of the Charleston at 101,024, a 4% growth over the population as of the 2000 census. The Charleston metropolitan area and North Charleston had a population of total of about 549,000, making Charleston the 76th largest city in the US. As of the 2000 census there are 96,650 people in the city, organized into 40,791 households and 22,149 families. Population density is 384.7/km² (996.5/mi²). Housing capacity is estimated at 44,563 housing units, with an average density of 177.4/km² (459.5/mi²). The racial makeup of the city is 63.08% White, 34.00% Black or African American, 1.24% Asian, 0.15% Native American, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 0.54% from other races, and 0.94% from two or more races. 1.51% of the population is Hispanic or Latino of any race. In addition, 23.2% have children under age 18 living with them, 36.0% are married couples living together, 15.2% have a female householder with no husband present, and 45.7% are non-families. 33.7% of all households are made up of individuals and 10.1% have someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older. The average household size is 2.23 and the average family size is 2.92. In Charleston, the population is spread out with 20.0% under the age of 18, 17.2% from 18 to 24, 28.8% from 25 to 44, 20.5% from 45 to 64, and 13.5% who are 65 years of age or older. The median age is 33 years. For every 100 females there are 89.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there are 87.2 males. The Charleston median income for a household in the city is $35,295, and the median income for a family is $48,705. Males have a median income of $32,585 versus $26,688 for females. The per-capita income for the city is $22,414. 19.1% of the population and 13.3% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 24.3% of those under the age of 18 and 13.9% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line. Notable Famous Charlestonians

|

|||

| All Content Copyright © 2002 - CharlestonDestinations.com |

|